Artificial Senses

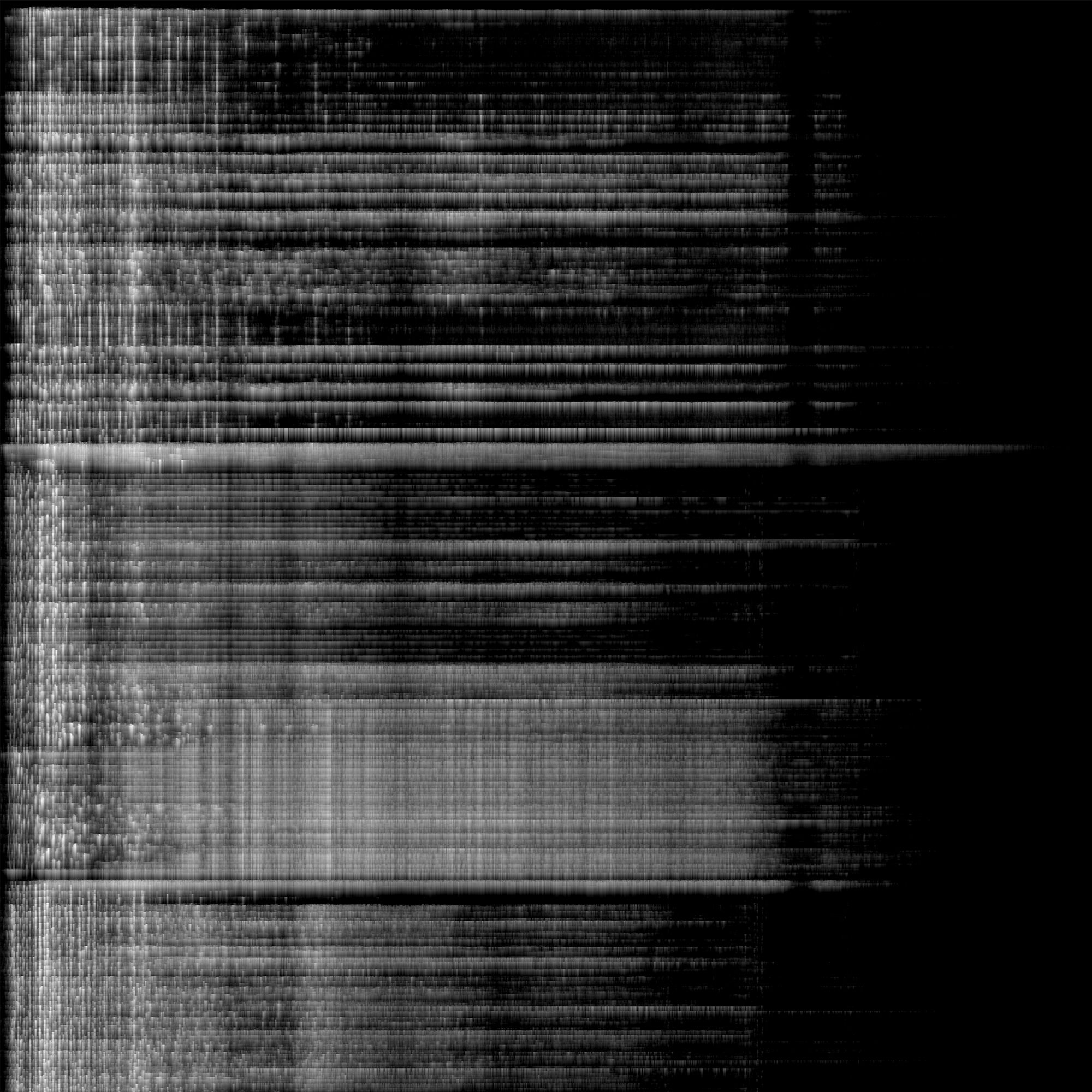

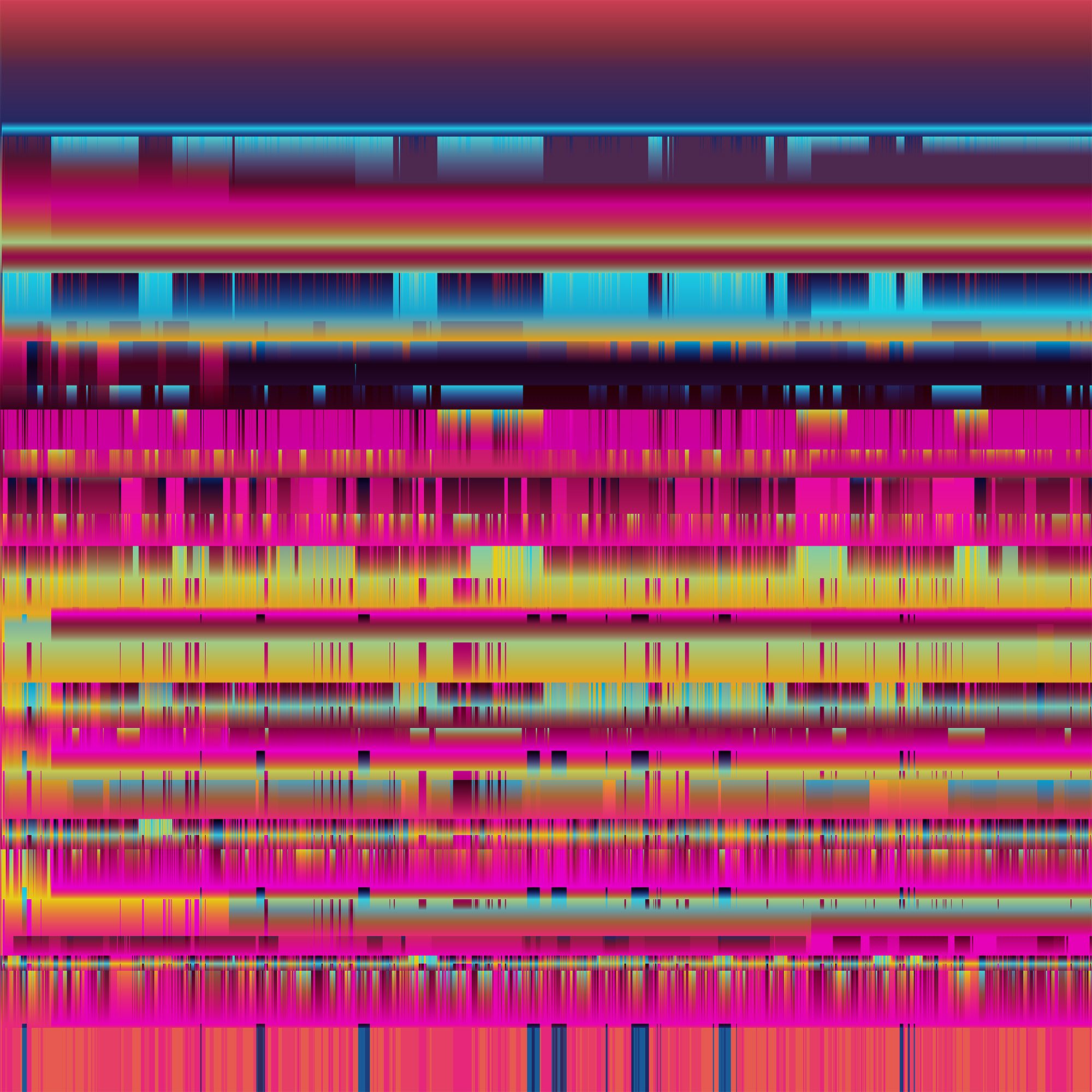

Artificial Senses visualizes sensor data of the machines that surround us to develop an understanding how they experience the world.- Time

- –

- Location

- Harvard Art Museums Lightbox Gallery

Contemporary culture is unimaginable without the machines that surround us every day. Our knowledge depends on Google search results, our music taste on the mixes Spotify creates for us and our consumption on Amazon recommendations. This strange new world became part of our reality in a very short timeframe. Interface design creates this natural feeling. But if we want to live with these devices and understand them, we cannot just rely on the machines becoming something easily understandable to us. We need to develop an understanding of how these devices experience our world.

The visualizations in Artificial Senses, which were shown in an installation at the Harvard Art Museums on August 12, 2017, and are now available as a web-native experience, explore a number of sensory domains: seeing, locating, orienting, and touching. Rather than yielding machine’s sensory data in ways that we intuitively grasp, however, these visualization try to get closer to the machine’s experience. And they show us a number of ways in which the machine’s reality departs from our own. With many of its sensors, for example, the machine is operating in a timescale that is too fast to understand; the orientation sensor returns data up to 300 times per second. This is not only too quick to manage to draw each of these values on the screen, but also too quick for us to comprehend. In most cases, to make these visualizations, the machine had to be tamed and slowed down for us to perceive its experience.

A second and more worrying finding is the similarity among many of the images. Seeing, hearing, touching are very different human experiences of the world, which lead to a wide variety of understandings, emotions or feelings. For the machine, they are very much the same. All of these senses are strings of numbers with a limited range of actual possibilities. While some of these sensory experiences—notably temperature—have long been given numerical value, their effects on us remain ineffable. Nowadays, however, not only temperature may be resolved to a number, but seemingly anything. But is this really true? Isn’t there something that our current measures of temperature cannot reveal about the entire spectrum from damp or crisp cold to feverish heat? And is this only a question of more data points? The entire orientation of a machine towards the world is mediated by numbers.

For the machine, reality is binary—a torrent of off and on. Any knowledge we accomplish through the machine about the world goes through the process of this abstraction. As we become more dependent on our machines, we need to understand these underlying boundaries of the form of abstraction that takes place.